Social enterprise and its ecosystem for sustainable development

by Erika Mattarella | Liberitutti scs / translation by Valentina Tudisco

Civic, generative, inclusive and supportive, a social enterprise by its very nature implies a scale of values that defines it not in quantitative terms, but first and foremost in qualitative terms. In other words, everything that we are most accustomed to associating with entrepreneurial initiatives in the era of globalisation, from the dematerialisation of labour, the relocation of production, the maximisation of profits and the normalisation of the cultural specificities of one’s networks of relations, is overturned in the concept of the effectiveness of this new economic actor.

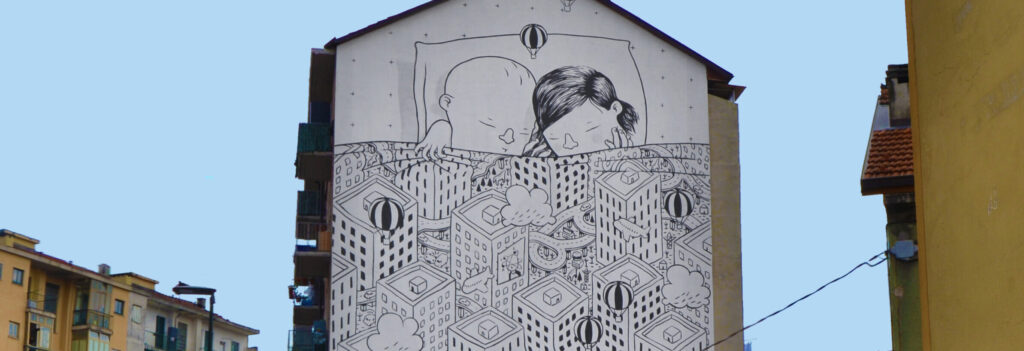

Therefore, it is not surprising that for most social enterprises, it is of strategic importance to identify their ecosystem of reference and reason from the perspective of a dynamic analysis of the social and geopolitical context in which they operate. In the great variety of economic sectors in which experiments of this kind take root, it is currently impossible to draw up a standard description of the perfect habitat for their development. For this very reason, the locations of social enterprises always tell a piece of their story, inescapably determining their objectives. Increasingly, the suburbs are becoming the ‘field of action’ of subjects and practices of innovation capable of activating processes of regeneration and enhancement of local resources, counteracting phenomena of impoverishment and value extraction (Giovanni Semi, Gentrification. All cities like Disneyland?, Bologna, 2015, Il Mulino).

Liberitutti has chosen this type of urban context as its ‘breeding ground‘ (Carlo Borzaga, Francesca Paini, Buon Lavoro. Social Cooperatives in Italy. Storie, valori ed esperienze di imprese a misura di persona, Milan, 2011, “Altraeconomia”), where a vast space accompanies phenomena linked to social tensions, difficulties in integration and lack of economic stability for planning freedom, an accurate position of subsidiarity concerning local authorities and the certainty of investing in the well-being of communities that will then come into play in terms of the social capital of the future.

In particular, Turin in the 1990s offered itself as a field of experimentation for a series of urban regeneration practices aimed at developing a recovery process that concerned urban architecture and infrastructures and considered the reconstruction of a fragmented social fabric as an integral part of the renewal process.

The broad participation of citizens in the process of re-functionalising entire areas left without an identity by phenomena linked to the crisis in the industrial sector, as well as new waves of migration, has borne fruit thanks to a vision based on significant investment plans such as the URBAN programme and the Special Suburban Programme.

Therefore, this type of public initiative emerged the need to engage in a more direct relationship between institutions and citizens. Thus, by acting as a connective membrane in the urban fabric, social enterprises have shown that they can play a growing role in offering services, working as a supplier to the public administration and mediating on the front of social cohesion and consequently economic development.

Using a new concept of training and business support in the perspective of learning by doing, accompanied by the experimentation of virtuous commercialisation networks, mechanisms of learning and organisational change have been set in motion even within the social enterprise itself; a democratic model of valorisation of existing competences and individual initiative from which unprecedented scaling models have emerged, capable of generating resources and competences also in favour of other subjects (service users, inhabitants of the neighbourhood, institutional referents, etc.).

Starting from this type of analysis, Liberitutti focused mainly on the northern area of the city, in a context suffering from a housing emergency, characterised by high unemployment rates and difficulties of integration between old and new citizens, as well as between permanent and temporary residents. From the first ten years of experience in the area, the Bagni Pubblici di Via Agliè was born and was set up as the Casa del Quartiere di Barriera di Milano, a place for the protagonism of civil society centred on the concept of “multi-identity”, capable of accelerating the social network according to collaborative criteria and promoting cultural opportunities as opportunities for empowerment and inclusion. The Glocal Factory project was then built on this know-how and is now in the start-up phase. It goes deeper into the community’s entrepreneurial potential, especially in the field of 2.0 craftsmanship, by sharing skills, spaces and tools and triggering new models of economic participation.

In a logic of place-based development, the social enterprise ecosystem revolves around the three axes that define its nature: an explicit mission of collective interest, an inclusive governance structure and the ability to create stable and continuous production processes (Borzaga C., Galera G., Franchini B., Chiomento S., Nogales R., Carini C. – eds. , Social Enterprises and their Ecosystems in Europe. Comparative synthesis report, Luxembourg, 2020 Publication Office of the European Union).

Leggi anche | Episodio 1 “Dialoghi sull’impresa sociale”

Leggi anche | Episodio 2 “Dialoghi sull’impresa sociale”